Rheta Grimsley Johnson -- The Atlanta

Journal Constitution 3/18/2001

BLUES BROTHERS

Along U.S.61, Mississippi

The echo was stupendous. Inside the

cavernous red barn on the Stovall Farms, where Muddy Waters

spent a

big, worried hunk of his life, Eddie Thomas sang the "Country Blues." He sang it the best he could, Muddy in mind.

big, worried hunk of his life, Eddie Thomas sang the "Country Blues." He sang it the best he could, Muddy in mind.

"Anything you want to say to Muddy,

Eddie?" Frank Thomas asked his brother when the song was

done.

Eddie knew what Frank meant. Muddy Waters

might have been there, singing from the gut, scaring sparrows

from the loft.

And that echo.

"It was like being in Notre Dame, or

some other cathedral," Eddie says.

All along historic Highway 61, from

Memphis to New Orleans, Eddie is singing and his brother Frank

recording. When they are done, there will be an album of 61

blues and jazz songs, recorded in places somehow appropriate to

the music.

They are like older Hardy Boys, solving

musical mysteries in their own back yard. Used to working

together, the Thomases can finish one another's sentences or

step back politely in fraternal deference as the other speaks.

There is mutual respect.

The Mississippi blues brothers, day by

day, have set up their rudimentary "studio" on a

Beale Street corner, in a Memphis city trolley, on stage at the

Orpheum Theater. They have recorded at the spot where the

Mississippi River levee broke during the Great Flood of 1927,

in pecan groves, on top of abandoned railroad beds, in deserted

depots, in silent cotton gins.

Forty songs down, 21 to go.

The Thomas brothers are determined to

finish by summer a CD that will give something extra to all

blues fans everywhere:

“They've heard the music, now we

want them to hear the land ..."

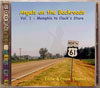

They are calling it "Angels on the

Backroads." Its the kind of project that needs a deadline.

Otherwise, well, you could keep trucking Highway 61 forever,

forgetting about the pressures peculiar to this century. In a

sense, Highway 61 is a road to the past. Or at least the part

of the past worth keeping.

Anywhere they find musical roots, the

Thomases dig in and record. They have done their homework,

mostly at the University of Mississippi's extensive blues

archives -selecting the songs, learning their histories,

delving into musical minutia such as exactly how each original

artist tuned his guitar.

Every Tuesday for five years Eddie, 54,

and Frank. 48, faithfully drove down to Ole Miss at Oxford from

their home in the red-brick Hundley Hotel in luka. All towns

need a substantial structure like the Hundley.

Up in that old hotel --lovingly restored

by the brothers -- is the Thomas studio, complete with

egg-crate insulation and a mixing closet shared with a

hot-water heater. Whenever a train rumbles by, the recording

business stops. But that's all right; every sentence

needs a period.

If you think about it, nearly every small

Southern town has a family like this one. Tremendously

talented, slightly eccentric, infinitely interesting. And

nothing rouses small-town curiosity like exceptional talent and

the rare ability to eschew a 9- to-5 job.

So when the Thomases recently announced a

preview of their work-in-progress to be held at noon in the

local library , the house was full. The crowd, to its

everlasting credit, was appreciative.

Iuka, the Thomases' home, is in

hardscrabble Hill Country, never to be confused with the rich

Deltaland. Yet the blues paved a less-traveled road between

regions, running like a deep, abiding river between towns and

topography. The Thomas brothers rode it.

Frank -- writer, photographer ,

independent filmmaker -- once won a gold medal at the Houston

Film Festival for a movie he made, with Eddie's help, starring

their effervescent mother, Billie.

Eddie, a trained pharmacist, can play any

instrument you put before him and has composed numerous songs

for Frank's films and other projects. Eddie got stage

experience as a young guitarist, performing as half a folk duo

during half a dozen summers at a Maine resort hotel.

"We were Eddie and Harold, the

laundry boy and the lifeguard, performing in the lounge,"

Eddie says. By the time the resort summers were over, Eddie had

quite a repertoire. With no formal training but high school

band, Eddie has that uncommon thing: a natural ability.

Together, a few years back, the brothers

made and marketed an audio guide for travelers along the nearby

Natchez Trace, a federal park that follows the old trade route.

This time the spotlighted byway is

Highway 61, a. strip of asphalt exalted to almost mystical

status by blues fans everywhere.

"A blues revival comes along about

every 10 years," Frank figures, "and we hope 'Angels

on the Backroads' will coincide with this one."

To that end, the two men headed west,

toward Memphis and the Mississippi Delta. They were a curious

sight. Eddie singing Frank Stokes' "Downtown

Blues" onboard car number 194 of the Main Street Trolley,

riding two loops of the city for 50 cents. Eddie blowing the

opening trumpet refrain of W.C. Handy's "Boogie Woogie on

St. Louis Blues" atop the roof of the Fall Building. Eddie

and Frank in the darkened Orpheum Theater, Eddie singing

Alberta Hunter's "Downhearted Blues."

On down into the Delta, into the

countryside, where a crop- duster almost drowned out Gus

Cannon's "Poor Boy a Long Way From Home" sung by

Eddie on a depot foundation in Tutwiler.

Eddie played Charlie Patton's

"Peavine Blues" inside a cotton gin on Dockery Farms.

"You can record in a cotton gin only when it's not

running; if it's running, you can't even record in the

town," Eddie laughs.

Curious onlookers have driven their John

Deeres close enough to watch the recording sessions, and on the

Memphis trolley a woman offered Eddie a Sunday singing job.

"I told her we already had a Sunday

gig, singing in the Methodist choir."

On the demo album, Eddie gives a little

of the history of each song and describes the performance site.

The narratives are purposely brief.

"It's the music, stupid!" a

sign in the studio reminds them.

"They definitely put in the hours

and a lot of hard work at the library," Ole Miss blues

archivist Ed Komara says. "The Thomas brothers are

tailoring

their project for general audiences, and

it'll be a good introduction for those interested in the blues

but who are not necessarily aficionados."

The land, the brothers say, is

inseparable from the music. The land is as rich and deep and

colorful as the songs first sung here. The land is responsible,

in a sense.

"I don't consider myself a blues

singer," Eddie readily admits.

He and Frank are more like missionaries,

sharing the word about the place, the people and the past.

"We grew up in the garden,"

Eddie says. Now it's harvest time.

Rheta Grimsley Johnson's commentaries are

distributed by King Features Syndicate.

M. Scott Morris - Northeast Mississippi

Daily Journal -- 3/9/2001

Singing Down Hwy. 61

Iuka brothers taking Mississippi blues

tour

A pair of Iuka brothers decided I to let

music guide them, and that's made for quite a journey.

Frank and Eddie Thomas are compiling a

collection of 61 songs with connections to places along Highway

61; from Memphis to New Orleans.

"Our whole idea was to tie the music

to the land," 54-year-old Eddie Thomas said. "We

wanted to make that connection."

The brothers have taken their equipment

on the road to record Memphis Minnie and Kansas Joe's

"When the

Levee Breaks" at the foot of the

levee northwest of Walls and "61 Highway Blues" by

Fred McDowell in a pecan grove on the side of Old Highway 61.

"We wanted to record these things on location," he

said.

"We wanted to get a feeling for

being there. We wanted to breathe the same air these musicians

breathed years ago."

High life

Frank Thomas, 48, handles the recording

and studio work while his brother performs the music.

"When at all possible, we record it

on location," Frank Thomas said. "We bring it back to

the studio and dub harmonies and voices."

In the case of W.C. Handy's "St.

Louis Blues," the final product only includes a few notes

from the field, while the rest was added at the brothers' Pearl

Street Studio in Iuka.

On a September evening in 1914, Handy and

his band debuted "St Louis Blues" on the Alaskan Roof

Garden atop the Falls Building in Memphis.

"There's nothing on top of the

building now. We got permission to go on the roof and record

the first phrase from the song on a trumpet, " Eddie

Thomas said. "The view is the same. The Mississippi

River was right there in front of us. It was amazing to

be at the same place where these notes first rang out."

Tracing the roots

Before hauling microphones around Memphis

and small Delta towns, the brothers buried themselves in

research to find the people, places and stories behind the

blues.

The brothers certainly don't fear

research, which they proved by producing "Natchez Trace: A

Road Through the Wilderness," a six audio tape tour of the

historic road.

"I read a zillion books on the blues," Eddie Thomas said. "I didn't

really think there were going to be so many people who were

significant to the story."

They learned about people like Son House,

a Robinsonville bluesman who influenced the likes of Muddy

Waters and Robert Johnson.

In "Land Where the Blues

Began," Alan Lomax describes "an aging grocery store

that smelt of licorice and dill pickles and snuff' where House

and his buddies stripped to their waists and played music.

The Thomas brothers found the place,

Clack's Store, and recorded House's "Shetland Pony

Blues."

“The first take we did a

mockingbird was singing. In every other take, the bird

didn't sing," Frank Thomas said. "We ended up using

the take with the bird. There was just something special about

it "

Miles to go

Many of the 40 recordings completed so

far include the sounds of trolley cars or honey bees behind

Eddie Thomas's guitar and vocals.

"It's a lot of fun, but it's pretty

exhausting, too," he said. "We're setting up the

equipment and taking it down and adjusting to whatever happens.

That's part of it. If the wind blows, the wind blows."

When spring arrives, the brothers plan to

hit the road again, following the music down to New Orleans for

the last 21 recordings.

Frank Thomas, who is writing the liner

notes for each recording and location, joked that the

completion date for the three-CD project was three years ago.

The deadline may be off, but there's

little chance the project will go unfinished. The music has a

pretty strong hold on the guys.

"Some of these people wrote their

songs 100 years ago and we're still influenced by them,"

Frank Thomas said. "Think of the power of that. Did

they know what they were doing or were they just living their

lives?"

His brother is pretty sure those old

musicians were just living everyday lives that ended up having

extraordinary impacts on music and the world.

"It's a real inspiration to

me," Eddie Thomas said. "You do feel these folks. I

would like to think of them saying, 'I appreciate you doing

this."'

|

||||||||||||

|

|

||||||||||||

|

|

||||||||||||

|

|

||||||||||||

|

ORDER

TOLL FREE

1-866-451-6047

|

|

|||||||||||

|

|

||||||||||||

|

|

||||||||||||

|

|

||||||||||||

|

|

||||||||||||

|

|

||||||||||||

|

|

||||||||||||

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

Geniuses might live near you, too

Iuka, Miss.-- A hometown genius is the

hardest to recognize. Prophets without honor without exception.

We all expect geniuses to live somewhere

exotic, somewhere else. They should look different, too, with

an Einstein shock of white hair, or at least Mark Twain's

dapper white suit. Geniuses should radiate.

They should speak in perfectly modulated

voices, like the late Barbara Jordan or David McCullough.

Geniuses should enunciate.

We certainly don't expect to pass their

houses daily on the way to the post office, the dry cleaner's,

the grocery store. We don't expect to claim them as friends.

Not once, but two or three times a day I

drive past the old hotel where brothers Frank and Eddie Thomas

live and work. On my way to pay the light bill or buy

toothpaste, I pass and wonder how they are doing, what they are

perfecting. Perfecting is their business.

The other day they ventured out to

Fishtrap Hollow, but I wasn't at home. That bothered me because

I always enjoy their company. Eddie sometimes sings for us;

Frank is a natural wit. We have a good time just swapping

stories.

But the day I missed them, Frank and

Eddie left on my porch proof positive of what I'd long

suspected: that they are geniuses. I don't use the word loosely

or with bias; I expect a lot of my geniuses.

For years, the Thomas brothers have been

working on an exceptional musical project, exceptional because

they are. They left behind the first installment: " Angels

on the Backroads, Volume 1, Memphis to Clack's Store."

Several years ago the brothers Thomas set

out from Memphis to New Orleans along old Highway 61. Eddie had

his guitar. Frank had his hand-held recorder. They have a

theory about the poets, the angels, who left so much music on

Mississippi's bluest highway.

Both brothers brought an encyclopedia's

worth of knowledge built from an exhaustive, fresh-eyed study

of the blues. During a five-year period, they researched and

recorded 61 pivotal blues songs along Highway 61, at locations

significant to each song.

Alberto Hunter's "Downhearted

Blues," for instance, Eddie performed at the Orpheum

Theater in Memphis during a break between shows. They recorded

Frank Stokes' "Downtown Blues" on the back bench of

car No. 194 of Memphis Main Street Trolley while it jostled and

jingled along. And for "Jim Jackson's Kansas City

Blues," they had but to follow old Jim's vision:

"So, we drive down a bumpy road to

the levee south of Lake Cormorant, Mississippi. Nine o'clock in

the morning and already hot, we climbed up on top of the levee

with our instruments and recording gear. The levee offers no

shade on a sunny day…"

Frank is the writer and the technical

whiz who somehow incorporated the rattles of the trolley, the

sundry street noises, echoes inside a plantation barn or a

cathedral.

Eddie is the musician. He plays, he

sings, he reconstructs in respectful renditions that never seen

presumptuous or false. His musical research was so complete, so

detailed, that he knew how each blues composer had tuned his

guitar for each song.

The production itself was kept simple,

true to its roots. No backup bands, no fancy studios. When

Eddie plays and sings the "Memphis Jug Blues" you

know it's also him on the jew's-harp. There will be four CDs in

all. The first is available for purchase at

www.AngelsOnTheBackroads.com. I don't usually attempt to sell,

but I make exceptions. If you think you know a little something

about the blues, you'll enjoy this take on roots music. If you

know nothing about the blues, this is a good primer.

The Thomas brothers now are working on a

companion and book that details their adventures along Highway

61 and educates at the same time. And there will be a 61-stop

concert tour at high schools in Tennessee, Mississippi and

Louisiana sponsored by the University of Mississippi's Center

for the Study of Southern Culture.

They always are working on something,

Frank and Eddie. Which might be the secret to becoming a

genius. You were born with abilities, but the devil is in the

honing.

And the angels, well, they are slightly

out of reach, in the darkness of our ignorance along the back

roads.

-----------------------------

Write to Rheta Grimsley Johnson, King

Features Syndicate, 235 E. 45th Street, New York, NY 10017.

ORDER

TOLL FREE

1-866-451-6047